原文地址:One Professor’s Attempt to Explain Every Joke Ever

By Joel Warner April 26, 2011 | 12:00 pm |Wired May 2011

Photo: Andrew Hetherington

The writer E. B. White famously remarked that “analyzing humor is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested and the frog dies.” If that’s true, an amphibian genocide took place in San Antonio this past January. Academics from around the world gathered there for the first-ever comedy symposium cosponsored by the Mind Science Foundation.

The goal wasn’t to tell jokes but to assess exactly what a joke is, how it works, and what this thing called “funny” really is, in a neurological, sociological, and psychological sense. As Sean Guillory, a Dartmouth College neuroscience grad student who organized the event, says, “It’s the first time a roomful of empirical humor researchers have ever gotten together!”

The first speaker at the podium, University of Western Ontario professor Rod Martin, began with a lament over the lack of comedy scholarship. He pointed out that you could fill a library with analyses of subjects like mental illness or aggression. Meanwhile, the 1,700-plus-page Handbook of Social Psychology—the preeminent reference work in its field—mentions humor once.

The crux of Martin’s argument involves semantics. It takes issue with the imperfect terminology we use to describe the emotional state that humor triggers. Standardizing language would help humor studies earn the respect of related fields, like aggression research. Martin exhorted his audience to adopt his preferred word for the “pleasurable feeling, joy, gaiety of mind” that humor elicits. Happiness, elation, and even hilarity don’t quite fit, to his mind. The best word, he said, is mirth.

For those curious about the physiology of humor, Helmut Karl Lackner of the Medical University of Graz, Austria, presented his research on the relationship between humor, stress, and respiration. By tracking breathing cycles and heart rates, he has determined that social anxiety makes things less funny. (Fittingly, he seemed nervous as he read his paper in halting English.) Nina Strohminger, a researcher at the University of Michigan, explained how she’s been exposing test subjects to unpleasant odors. She extolled the virtues of a spray called Liquid Ass, which can be purchased at fine novelty stores everywhere. (Her conclusion: Farts make everything funnier.) The audience members take the subject of amusement very seriously, yet they couldn’t help but chuckle at this.

Other speakers peppered their talks with multivariate ANOVAs and mesolimbic reward systems. Some presented research on whether people with Asperger’s syndrome get jokes and how to determine the social consequences of put-downs. But as the sessions wound on, no one had addressed the underlying mechanism of comedy: What, exactly, makes things funny?

That question was the core of Peter McGraw’s lecture. A lanky 41-year-old professor of marketing and psychology at the University of Colorado Boulder, McGraw thinks he has found the answer, and it starts with a tickle. “Who here doesn’t like to be tickled?”

A good number of hands shot up. “Yet you laugh,” he said, flashing a goofy grin. “You experience some pleasurable reaction even as you resist and say you don’t like it.”

If you really stop to think about it, McGraw continued, it’s a complex and fascinating phenomenon. If someone touches you in certain places in a certain way, it prompts an involuntary but pleasurable physiological response. Except, of course, when it doesn’t. “When does tickling cease to be funny?” McGraw asked. “When you try to tickle yourself … Or if some stranger in a trench coat tickles you.” The audience cracked up. He was working the room like a stand-up comic.

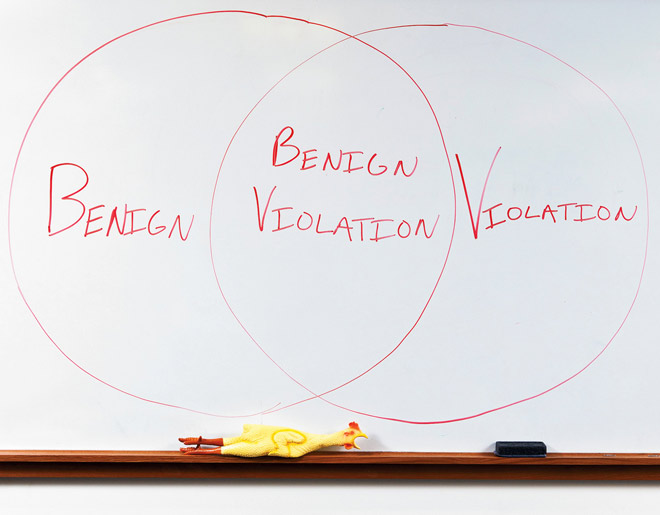

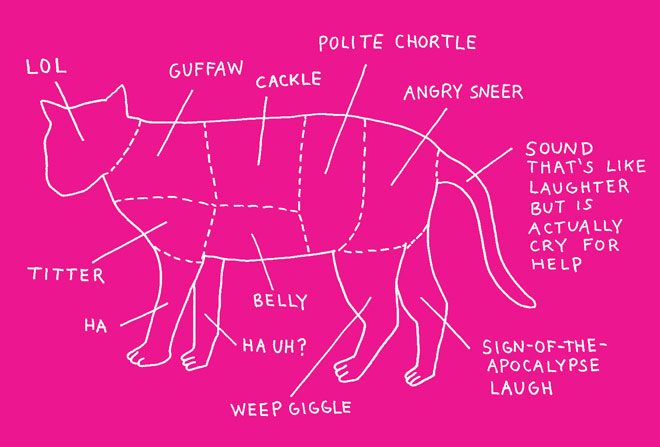

Many would assert that this tickling conundrum is the perfect evidence that humor is utterly relative. There may be many types of humor, maybe as many kinds as there are variations in laughter, guffaws, hoots, and chortles. But McGraw doesn’t think so. He has devised a simple, Grand Unified Theory of humor—in his words, “a parsimonious account of what makes things funny.” McGraw calls it the benign violation theory, and he insists that it can explain the function of every imaginable type of humor. And not just what makes things funny, but why certain things aren’t funny. “My theory also explains nervous laughter, racist or sexist jokes, and toilet humor,” he told his fellow humor researchers.

Photo: Andrew Hetherington

Photo: Andrew Hetherington Coming up with an essential description of comedy isn’t just an intellectual exercise. If the BVT actually is an unerring predictor of what’s funny, it could be invaluable. It could have warned Groupon that its Super Bowl ad making light of Tibetan injustices would bomb.The Love Guru could’ve been axed before production began. Podium banter at the Oscars could be less excruciating. If someone could crack the humor code, they could get very rich. Or at least tenure.

It’s a wintry February afternoon in Boulder and a 53-year-old tech worker named Kyle fires up a joint he obtained from a medical marijuana dispensary. After smoking his medicine and waiting 15 minutes for it to take effect, Kyle opens a 10-page printed questionnaire. He sees a Photoshopped image of a man picking his nose so vigorously that his finger pokes out of his eye socket. “To what extent is this picture funny?” the survey asks, inviting Kyle to rate the picture on a scale of 0 to 5. He gives it a 3.

Kyle is one of 50 or so marijuana aficionados who have volunteered to take part in a study run by McGraw’s laboratory at CU-Boulder—the Humor Research Lab, or HuRL for short. Founded in 2009, HuRL is unorthodox, to put it mildly, even for academia. But McGraw is doing serious enough work at HuRL to have earned two grants from the Marketing Science Institute, a nonprofit funded by respectable organizations like Bank of America, Pfizer, and IBM. The professor and a team of seven student researchers have been asking test subjects to gauge whether Hot Tub Time Machine is funnier if you sit close to the screen or far away. They show subjects a YouTube video of a guy driving a motorcycle into a fence over and over again to see when it ceases to be amusing.

Photo: Andrew Hetherington

Photo: Andrew Hetherington The medical marijuana patients will help HuRL researchers answer a momentous question: Can smoking pot make things more funny? The answer may seem forehead-smackingly obvious, but according to McGraw it’s impossible to know for sure without applying scientific rigor. “Your intuition often leads you astray,” he says. “It’s only within the lab that you can set different theories against one another.” McGraw believes that the tests will ultimately prove that marijuana does in fact make broad sight gags more funny. But he needs more data before he can be certain. He’s begun soliciting input from more potheads through ’s crowdsourcing marketplace, Mechanical Turk.

McGraw didn’t set out to become a humorologist. His background is in marketing and consumer decisionmaking, especially the way moral transgressions and breaches of decorum affect the perceived value of things. For instance, he studied a Florida megachurch that tarnished its reputation when it tried to reward attendees with glitzy prizes. The church’s promise to raffle off a Hummer H2 to some lucky congregant was met with controversy in the community—what the hell did that have to do with eternal salvation? But when McGraw related the anecdote at presentations, it prompted laughter—a holy Hummer!—rather than repulsion. This confused him.

“It had never crossed my mind that moral violations could be amusing,” McGraw says. He became increasingly preoccupied with the conundrum he saw at the heart of humor: Why do people laugh at horrible things like stereotypes, embarrassment, and pain? Basically, why is Sarah Silverman funny?

Philosophers had pondered this sort of question for millennia, long before anyone thought to examine it in a lab. Plato, Aristotle, and Thomas Hobbes posited the superiority theory of humor, which states that we find the misfortune of others amusing. Sigmund Freud espoused the relief theory, which states that comedy is a way for people to release suppressed thoughts and emotions safely. Incongruity theory, associated with Immanuel Kant, suggests that jokes happen when people notice the disconnect between their expectations and the actual payoff.

Photo: Andrew Hetherington

Photo: Andrew Hetherington But McGraw didn’t find any of these explanations satisfactory. “You need to add conditions to explain particular incidents of humor, and even then they still struggle,” he says. Freud is great for jokes about bodily functions. Incongruity explains Monty Python. Hobbes nails Henny Youngman. But no single theory explains all types of comedy. They also short-circuit when it comes to describing why some thingsaren’t funny. McGraw points out that killing a loved one in a fit of rage would be incongruous, it would assert superiority, and it would release pent-up tension, but it would hardly be hilarious.

These glaringly incomplete descriptions of humor offended McGraw’s need for order. His duty was clear. “A single theory provides a set of guiding principals that make the world a more organized place,” he says.

McGraw and Caleb Warren, a doctoral student, presented their elegantly simple formulation in the August 2010 issue of the journal Psychological Science. Their paper, “Benign Violations: Making Immoral Behavior Funny,” cited scores of philosophers, psychologists, and neuroscientists (as well as Mel Brooks and Carol Burnett). The theory they lay out: “Laughter and amusement result from violations that are simultaneously seen as benign.” That is, they perceive a violation—”of personal dignity (e.g., slapstick, physical deformities), linguistic norms (e.g., unusual accents, malapropisms), social norms (e.g., eating from a sterile bedpan, strange behaviors), and even moral norms (e.g., bestiality, disrespectful behaviors)”—while simultaneously recognizing that the violation doesn’t pose a threat to them or their worldview. The theory is ludicrously, vaporously simple. But extensive field tests revealed nuances, variables that determined exactly how funny a joke was perceived to be.

McGraw had his HuRL team present scenarios to hundreds of CU-Boulder students. (Some were bribed with candy bars to participate.) Multiple versions of scenarios were formulated, a few too anodyne to be amusing and some too disgusting for words. Ultimately, McGraw determined that funniness could be predicted based on how committed a person is to the norm being violated, conflicts between two salient norms, and psychological distance from the perceived violation.

Illustration: Demetri Martin

The ultimate takeaway of McGraw’s paper was that the evolutionary purpose of laughter and amusement is to “signal to the world that a violation is indeed OK.” Building on the work of behavioral neurologist V. S. Ramachandran, McGraw believes that laughter developed as an instinctual way to signal that a threat is actually a false alarm—say, that a rustle in the bushes is the wind, not a saber-toothed tiger. “Organisms that could separate benign violations from real threats benefited greatly,” McGraw says.

The professor was able to plug the BVT into every form of humor. Dirty jokes violate social norms in a benign way because the traveling salesmen and farmers’ daughters that populate them are not real. Punch lines make people laugh because they gently violate the expectations that the jokes set up. The BVT also explains Sarah Silverman, McGraw says; the appalling things that come out of her mouth register as benign because she seems so oblivious to their offensiveness, and “because she’s so darn cute.” Even tickling, long a stumbling block for humor theorists, appears to fit. Tickling yourself can’t be a violation, because you can’t take yourself by surprise. Being tickled by a stranger in a trench coat isn’t benign; it’s creepy. Only tickling by someone you know and trust can be a benign violation.

McGraw and the HuRL team continue to test the theory even as they begin to deploy it in the real world. They’ve partnered with mShopper, a mobile commerce service, to see whether BVT-tested humor can make text-message product offers more compelling. They’ve also launched FunnyPoliceReports , which aggregates law enforcement dispatches that are likely to amuse readers, such as a woman who called the cops when she was sold fake cocaine.

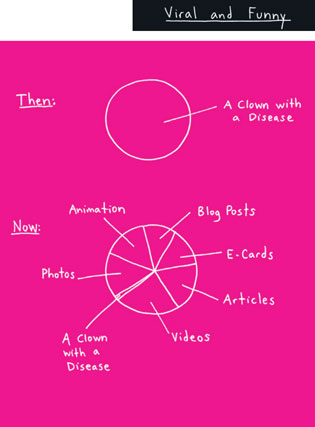

If the website sounds sort of like FAIL Blog, that’s no accident. McGraw knows Ben Huh, CEO of the Cheezburger Network, who has been using HuRL’s findings to help determine what content and features have the potential to be the next big meme. The lolcats baron points to a recent post about a priest cracking down on cell phones in church after a parishioner’s “Stayin’ Alive” ringtone went off during a funeral. “The benign violation theory applies to that,” Huh says. “I’m a guy who makes his living off of Internet humor, and McGraw’s model fits really well. He’s just a lot more right than anyone else.”

Photo: Andrew Hetherington

Photo: Andrew Hetherington The conference in San Antonio was the first time McGraw presented his theory to other humor researchers. His well-honed delivery gets a lot of laughs, but his theory ultimately receives the same polite applause as everything else. There are no stunned looks of amazement in the audience, no rumblings of a field torn asunder.

Maybe it’s because a discipline that can’t even agree on what to call the response elicited by humor isn’t ready for a universal theory of humor. At this point, there’s still no single way to measure it. (The International Society for Humor Studies lists 14 tests and scales for measuring humor, from the Multidimensional Sense of Humor Scale to the Humorous Behavior Q-Sort Deck.)

The BVT also has its fair share of detractors. ISHS president Elliott Oring says, “I didn’t see many big differences between this theory and the various formulations of incongruity theory.” Victor Raskin, founder of the academic journal Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, is more blunt: “What McGraw has come up with is flawed and bullshit—what kind of a theory is that?” To his mind, the BVT is a “very loose and vague metaphor,” not a functional formula like E=mc2. He’s also quick to challenge McGraw’s standing in the tight-knit community of scholarship: “He is not a humor researcher; he has no status.”

McGraw’s lecture did impress Robert Mankoff, cartoon editor at The New Yorker, who also gave a presentation in San Antonio. (Fun fact: New Yorker cartoons must endure the infamous rigors of the magazine’s fact-checkers; just because a cartoon bluebird can talk doesn’t mean it shouldn’t resemble a genuine Sialia.) After the symposium ended, he offered to provide HuRL with thousands of caption-contest entries to examine. Mankoff says he admires McGraw’s work, “and I admire him even more for having the balls to take his theory on the road as stand-up.” But he also has a caveat for McGraw and other humor scientists: “All these theories are so general that they’re of no use when you’re trying to craft a good cartoon.” He cites one that he’s particularly fond of, an illustration of a Swiss Army knife featuring nothing but corkscrews. The caption reads “French Army knife.” No Venn diagram, he says, has ever produced a joke like that.

Illustration: Demetri Martin

Illustration: Demetri Martin It’s a half hour to showtime at Denver’s Paramount Theatre and McGraw is milling around in the lobby, hoping to get green-room access to the comedian Louis CK. The prof is convinced that his theory works in the lab, and he’s increasingly interested in testing it in the wild. Kind words from Huh and Mankoff are fine, but the endorsement of a comedian with his own eponymous show on cable would be invaluable. CK is one of McGraw’s favorites. “I am fascinated by his ability to make things funny that I wouldn’t have thought could be funny,” McGraw says, “how he portrays his role as a father in an unflattering way.”

McGraw gets the go-ahead, and with curtain time closing in, he’s soon sitting in the presence of his idol. The comedian slumps into a chair, the toll of weeks on the road apparent on his face. Knowing that he has only a few minutes, McGraw gives a nutshell version of his well-honed spiel. He lays out the BVT and describes the tickling conundrum that killed at the humor symposium. But CK cuts him off. “I don’t think it’s that simple,” he says, directing as much attention to a preshow ham sandwich as to McGraw. “There are thousands of kinds of jokes. I just don’t believe that there’s one explanation.”

Oof, tough room. His research dismissed, McGraw casts about for another subject of inquiry. Luckily, he’d polled fellow attendees for questions while waiting for an audience with CK. “A woman in the lobby wants to know how big your penis is,” he says.

CK cracks the faintest of smiles, shakes his head. “I am not going to answer that.”

“I wouldn’t either,” McGraw says. With a chuckle he adds, “But I’ve heard that if you don’t answer that, it means it’s small.”

Photo: Andrew Hetherington

Photo: Andrew Hetherington The silence that follows is so thick you could pound in a nail and hang a painting from it. That last remark is a violation, and it isn’t benign. McGraw changes the subject again. “So, you’re friends with Chris Rock?” he says. He wonders whether CK could ask Rock for seed funding, even offering to rename his facility the Chris Rock Humor Research Lab (CRoHuRL?).

“No,” CK says. This time, there’s no smile.

Sensing that his time is up, McGraw heads for the door. He did get one valuable takeaway: “My approach to this sort of research needs to be more professional.”

When the show begins a bit later, Louis CK has shed all vestiges of his preshow reticence. It takes only a couple of jokes about slavery to get McGraw chuckling in his front-row seat. By the time the comedian describes having a bizarre dream about Gene Hackman, the professor is completely overcome. His body jerks uncontrollably as he emits a series of deep, braying laughs that end with a little nasal honk. This is full-on mirth.

The other people in the theater are also in hysterics. They don’t know exactly why, and maybe it doesn’t matter.

Joel Warner () is a staff writer for Westword

转发至微博

转发至微博

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号